In her essay ‘Art’, Smith follows a nun and her school-group round the National Gallery. ‘How do people see pictures?’ she wonders. ‘It was such a hot afternoon, the question is such a lazy one’. Smith eavesdrops; she lolls; she daydreams. She pores over the catalogue:

Catalogues, as you see, have a language of their own, terse and evocative: “S. John, centre, facing right, wearing a lavender-grey dress. Left: S. Francis, profile right, S. Lawrence, in grey, with rose orange collar… All seated full-length on a marble seat…along the bottom of the picture a little hedge of herbs…” (‘Art’ in London Guyed (London, 1938), p. 159)

Most of the paintings Smith mentions match up with the National Gallery’s collection.

Lolling alone against Elsheimer’s “St Lawrence”…(157)

‘…And if I do not wish to be forever solitary, but must have figures for my landscape more substantial than a tearful ghost, I will steal from Ingres his Roger and Angelica, from Daumier his Bathing Boys…’ (162)

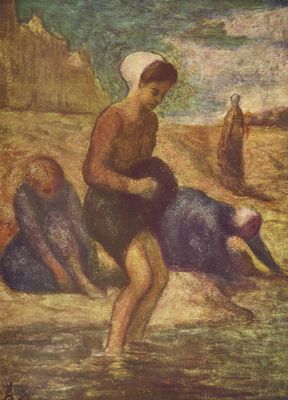

But where – and what – is the third painting Smith mentions here: ‘Daumier’s Bathing Boys’? There is no painting of that name by Honoré Daumier in the National Gallery. Nor can I find any sign of it in the Daumier Register. There exists a ‘Bathing Girls‘ by Daumier:

There’s ‘The Bathers‘…

…another ‘The Bathers‘…

But no ‘Bathing Boys’, even allowing for all the French variants of Daumier’s titles. And anyway the National Gallery only holds Daumier’s ‘Don Quixote and Sancho Panza‘ – and no paintings at all called ‘Bathing Boys’, by any artist.

Why is Smith importing a non-existent painting into the National Gallery?

On one level, ‘Art’ is obviously an essay about good ways and bad ways to experience art. ‘How do people see pictures?’ Smith asks, and isn’t impressed with the choices of the people in the gallery. The nun hurries her charges around in a group – to which Smith responds, darkly, ‘The way to look at pictures is not in groups, and not in a hurry’. She also takes exception to ‘the informer’: people who pester their friends with loud comments about the art are ‘at all costs to be avoided’.

So we could see Smith’s imprecision about Daumier as a stance against informer-type pedantry. On a hot afternoon, she hints, our response to art should instead be lazy, lolling, generously impressionistic.

I will steal from Ingres his Roger and Angelica, from Daumier his Bathing Boys…’ (162)

Smith imagines stealing figures from here and there; populating her imagined landscapes with Ingres and Daumier. And this might be an act of resistance against the finickiness of the catalogue – ‘S. John, centre, facing right, wearing a lavender-grey dress’ – which focuses on facts rather than instinctive, playful responses. Smith subverts this factual, systematised approach to art by illegitimately creating and importing a painting which has no place within it.

There’s some truth in that idea. But this reading misses the mark a little. Smith likes the art catalogue. She calls its language ‘terse and evocative’. She is drawn, I think, by the catalogue’s combination of the mundanely precise – ‘centre, facing right’ – and the not-entirely-successfully poetic – ‘a lavender-grey dress’, ‘rose-orange collar’. When she cites the entry, she is relishing it rather than simply mocking it.

‘Catalogue’ is from the Greek καταλέγειν: to choose or pick out. And the catalogue entry on ‘Seven Saints’ depends, for both its interest and its practical value, on acts of capture and selection. For the ‘informer’ in the gallery, the catalogue acts as a travel-guide, instructing us on what is worthy of ‘careful comment’. For Smith, its charm derives from the absolute mundanity of details it chooses to focus on. What is there to say about an orange collar and a little hedge of herbs?

The catalogue entry represents an establishment view of art. But it can only fulfil that role by undertaking small acts of theft. From the painting it steals the lavender-grey dress, the rose orange collar, the marble seat; it reconfigures them into its own little work of art. In the catalogue, pedantry and romantic, stylised half-truth occupy the same space. Just as, for Smith, the factually-present ‘St Lawrence’ sits side by side with Daumier’s fictional ‘Bathing Boys’.

So holes remain in Smith’s theory of art: a gap on the wall where ‘Bathing Boys’ should be. Subversion does not separate wholly from the establishment. And Stevie Smith opts out, in the end, of forcing us to decide how people see (or should see) pictures. ‘It was such a hot afternoon’, she excuses herself, ‘the question is such a lazy one’.